Preparing for the EU Pay Transparency Directive | Download our E-book for free

The Unadjusted Pay Gap vs. the Adjusted Pay Gap

This article has been updated. It was previously published on the 28th of November 2022.

Although we often talk about “THE” gender pay gap, there are actually two types of pay gap: unadjusted and adjusted. This article lays out the differences. We also talk about which type of pay gap to measure in different situations and how these pay gaps are calculated.

The gender pay gap between men and women in the U.S. is 23.7%. But which gap are we talking about?

You may have seen the statistic that on average, the ‘gender pay gap’ is close to 24% in the United States (24 cents/dollar); 21% in the United Kingdom (21 pence/pound); or 29% in Germany (29 cents/euro). According to the World Economic Forum’s 2023 Gender Gap Report, only a quarter of the 146 countries evaluated had pay gaps of 20%-30%, and even fewer (two) had an overall earned income gap of lower than 20%.

You may have also heard people argue that the gender pay gap is a myth—that its prevalence is over-hyped or nonexistent because this statistic fails to account for certain factors. For instance, women often work fewer hours due to family caretaking roles, or they may go into lower-paying careers.

In fact, there is truth to both of these statements: There is a large gender gap in average wages and in median lifetime earnings. And the 24 cents-on-the-dollar measurement doesn’t account for all the nuances of gender-related differences in employment.

This is the reason there are two types of pay gaps: unadjusted and adjusted.

How do the unadjusted and adjusted pay gaps differ?

The unadjusted pay gap (also referred to as the uncontrolled pay gap) measures the average difference in pay between men and women. This is the 24-cents-on-the-dollar statistic.

The adjusted pay gap (also called the controlled pay gap or equal pay gap) measures the difference in pay between women and men after accounting for factors that determine pay, such as job role, education, and experience.

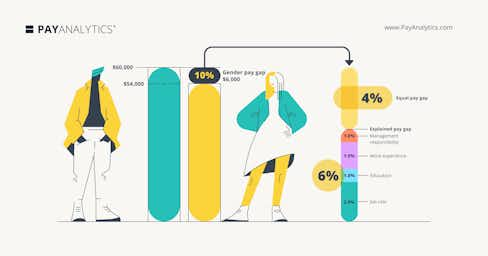

Let’s take a company – we’ll call it ACME X – where the average man makes $60,000 and the average woman makes $54,000. This makes the company’s unadjusted pay gap 10% ($6,000). However, let’s say that ACME X runs a regression analysis that accounts for differences in pay factors and calculates its adjusted pay gap at 4%.

Even though this 4% adjusted pay gap is smaller in magnitude relative to the 10% unadjusted pay gap, it likely indicates discriminatory pay practices. It reflects that, on average, a woman within ACME X can expect to be paid 4% less than a man with the same job role, education, and experience. If a female employee with average pay stays at ACME X for 10 years, her total earnings over that period will be $24,000 less than her male colleagues’. She is far less able to afford to buy a home or weather a financial emergency.

ACME X’s 10% unadjusted pay gap may be a result of the presence of more men in higher paying roles and/or more women in lower-earning roles. It’s very concerning because an unadjusted pay gap often indicates a lack of equal access to opportunity. Even if you have a 0% adjusted pay gap, which is measuring pay equity, you could still have a non-0% unadjusted pay gap—which speaks to employee diversity and representation rates across the organization.

For instance, let’s say this company’s unadjusted pay gap is driven by the fact that most higher-paid jobs with management responsibilities are held by men. In this scenario, ask why women are rarely promoted or hired into management or higher-earning positions within the organization.

The unadjusted pay gap or the adjusted pay gap: Which do you measure?

The answer to this question is “both.” Each of the two pay gap measurements give you different useful information about your workforce, your pay structure, and pay equity within your organization.

Regulations are one main reason for measuring a pay gap. Local and national laws vary in what they require: They may ask for the unadjusted (or uncontrolled) pay gap, the adjusted (controlled) pay gap, or both. In some cases, the regulations even specify how the pay gap should be calculated.

For more specific information about your country and region, please see our continually updated local resource page.

Even in the absence of regulations, companies are increasingly measuring their pay gaps as a fundamental part of their pay equity practice. Pay gap analysis can be key to DE&I efforts. This work often focuses on addressing the reasons for the unadjusted pay gap. So after ACME X starts closing its 4% adjusted pay gap, its longer-term DE&I work might involve making sure that all employees have equal access to promotion opportunities within the company. This will eventually lead to more women in management roles and further decrease its unadjusted pay gap.

How to calculate the pay gaps: Simple math and regression analysis

The unadjusted pay gap is a straightforward calculation of the percentage difference between the average pay of each gender.

As we mentioned earlier, the adjusted pay gap is calculated using regression analysis. The method our PayAnalytics software uses is called log-linear regression. This is the standard approach used by many pay equity software firms, regulatory agencies, and academic researchers. Specifically, a log-linear regression regresses the natural log of wages on gender and other pay factors like experience, education, location, and tenure. In a nutshell, a regression analysis—rather than averaging out the pay of all employees—accounts for all relevant factors that influence pay, then shows you whether gender bias is causing a pay difference between genders and how big that difference is.

When we think about compensation, we’re often dealing with massive datasets of individuals in different roles, with differing levels of tenure, who are perhaps globally dispersed within sprawling organizations. Regression analysis allows us to parse that data to extract meaningful insights into the variables that matter.

Regression analysis is not the only statistical analysis used to explain variations in pay; it is, however, the most nuanced and flexible approach to measuring pay gaps and yields richer insights into your pay structures, and the complex reasons behind them. While other methods—such as the “means and medians” approach—can guide an overarching conversation about diversity, equity, and inclusion in the workplace, performing regression analysis to calculate the adjusted pay gap really shows you how different factors (experience, education, performance) contribute to pay, and how those contributions may differ across departments and roles. Regression accounts for the extent to which “valid” variables like experience contribute to pay and determines when and where “invalid” factors, like gender and race, affect pay.

How PayAnalytics’ pay equity software solution can help

PayAnalytics is a comprehensive solution that shows you what you need to know about pay equity within your organization – from simple calculations to more complex analyses and tracking.

Want to learn more about how you can run an analysis that ensures equal pay for work of equal value? If your organization is new to pay equity analysis, we’ve written a short article for first-timers. Or if you need to stay up to date on pay equity and pay transparency regulations in your part of the world, check out our local resources page.

If you are interested in knowing more about specific features of the PayAnalytcs solution (e.g. Pay equity analysis or Workforce analytics) you can have a look at our product feature overview page.

We invite you to book a 1:1 meeting with one of our pay equity specialists to see how we can help you on your pay equity journey.